This is a comparison and contrast between two common proteinopathies (Alzheimer’s disease & Parkinson’s disease), discussing clinical symptoms, epidimiology and pathological hallmarks.

Main body

The present view takes proteinopathy as an umbrella term for the neurodegenerative disorders caused by the accumulation of misfolded protein, which is attributable to the conformational error of the protein (Bayer, 2015, Lanuti, 2020) These aggregated proteins were verified to gain typical amyloid features (Virchow, 1854) which means the “starch” conformation. In this case, these proteins might not only lose their original normal function but also gain toxicity (Luheshi et al., 2008). Speaking of proteinopathies, two diseases must be mentioned: One is Parkinson’s disease (PD), the most famous progressive neurodegenerative diseases associated with motor as well as nonmotor deficits, which is known as the second common neurodegenerative disorder, (Capriotti & Terzakis, 2016; Simon et al., 2020; Hayes, 2019); the other one is Alzheimer’s disease (AD), one of the most major reason for dementia, the most common neurodegenerative disorder (Lane, Hardy & Schott, 2018). There are around one billion sufferers around the world who are suffering both physical and psychological agony from these neurodegenerative disorders in 2019 (Bulck et al., 2019). Various factors, for instance genomic, epigenomic, metabolic, or environmental factors (Bulck et al., 2019), are shown to have an impact on PD and AD in a permutation and combination way. Here this essay will go into detail about these two common proteinopathies in three aspects: clinical symptoms, epidemiology and pathological hallmarks.

In terms of clinical symptoms between PD and AD, multiple similar as well as differing pathological phenotypes can be identified, which is treated under the comparison and contrast between PD and AD (Table 1). PD and AD are both irreversible progressive, degenerative diseases meaning the symptoms will gradually become more severe as the stages develop. The most obvious problems about patients’ cognitive and psychiatric symptoms come first as we consider these neurodegenerative diseases. As far as we know, AD is well-known for its influence on memory, academically called amnesia which was first conceptualized as memory loss in 1763 by Sauvagues (Langer, 2019). Most of the advanced AD sufferers are reported to have Amnesia symptoms, accounting for fifty per cent to seventy per cent of all patients with dementia (Burns & Iliffe 2009), while it seldomly happens to PD patients. Only the most severe PD sufferers are reported to experience similar amnesia symptoms (Querfurth & LaFerla, 2010). At the memory level, patients with AD not only have amnesia but also often experience memory distortions (El Haj et al. 2020, Younan et al., 2020), such as having comprehensive and vivid memories of episodic occurrences that have never been observed. AD symptoms are generally considered as an essential impairment of episodic memory (Younan et al., 2020), while one’s attention is compromised on AD’s early stage as well, especially in those with early age onset and atypical syndromes (Malhotra, 2018). One feature of AD is that the symptoms are accompanied by severe attentional impairment frequently which is linked with other neurodegenerative disorders as well (Malhotra, 2018). It is suggested that PD patients suffer more depression and anxiety (Sveinbjornsdottir, 2016) than AD patients, which may be concluded to the inconsistency between one’s movements and willingness.

Apart from memory problems for AD and PD, some other motor symptoms can also put huge inconvenience to one’s life. PD patients are reported to have three main symptoms which are tremor, bradykinesia and rigidity (Hayes, 2019). Tremor means shaking, especially after a short pause of a postural movement. Bradykinesia implies a slower movement than normal action which may cause difficulties for some ordinary tasks like walking or doing dishes. Rigidity or spasticity refers to muscle stiffness, which is academically called dystonia (Tolosa & Compta, 2006). Unlike those symptoms in AD, these three main symptoms in PD are more relying on the neuromuscular connection so that these are all related to muscle control abnormality which is the direct result of neurodegeneration the same as AD (McGregor & Nelson, 2019). Similarly, AD patients also suffer motor problems like dysphagia referring to the difficulty in swallowing, which is also reported in eleven to eighty-one per cent of PD patients (Takizawa et al., 2016). Patients with AD gradually lose cognitive functions until they reach the final stage of the disease, which is characterised by full failure of control over body functions (Boccardi et al., 2016).

Regarding the nonmotor symptoms, anosmia (the sense loss of smell) and ageusia (the sense loss of taste), are common in PD. And the equivalent olfactory loss is also observed in AD (Doty 2012), which may be contributed to the shared pathological features. It may be corroborated that the olfactory loss is significantly linked to cognitive level (Tarakad & Jankovic, 2017). This is different from PD: AD patients show more cognitive impairments. There occur some other cognitive problems in AD more than memory. For example, one type of language disorder, aphasia is usually related to AD owing to the damage of frontal, temporal, or parietal language cortices. And these aphasias caused by AD accounts for nearly thirty per cent of primary degenerative aphasias (Teichmann & Ferrieux, 2013). The problems are not only about daily life activity but also about the biological clock. Sleep disturbances and sleep disorders come to be big problems for AD and PD patients since these are long term and progressive diseases. (Peter-Derex, 2015). Sleep disorders, on the other hand, is reported to be linked to an increased risk of AD. Both situations have a negative impact on one’s attention (Hennawy et al., 2019). Insomnia and exhaustion are also the following side effects of sleep disorders. Together with physical discomfort, those symptoms above can cause psychological discomfort in PD when comparing PD and AD. Neuralgia has become a severe problem for patients. There are five main forms of pain are documented in PD sufferers which are separately dystonia, musculoskeletal pain, nerve or nerve root pain, primary or central pain and akathisia with some samples (Rana 2013).

To sum up, AD and PD symptoms are generally different, but these share some key features at the same time. PD patients are more likely to have primarily motor abnormalities, whereas AD patients normally experience dementia and cognitive impairment (Meireles & Massano 2012). The neuronal death is a typical feature of both illnesses, the autopsy histopathology of the brains from AD and PD patients are distinct in each instance and diverse from one another (Ganguly et al., 2017). AD focuses more on cognitive symptoms while PD focus more on physical symptoms even though these can be divided into motor and nonmotor symptoms.

Table 1. Comparison and contrast table of Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease in symptoms, causes, onset age, treatment, and lifespan expectancy.

| AD | PD | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical symptoms | Amnesia (El Haj et al., 2020) Impairments of attention (Malhotra, 2018) Disorder of episodic memory (Younan et al., 2020) Memory distortions (El Haj et al. 2020) Dysphagia (Boccardi et al., 2016) Dysphasia (Teichmann & Ferrieux, 2013) Sleep disruption and sleep disorders (Hennawy et al., 2019) | Tremor Bradykinesia Rigidity (NHS, 2019) Loss of balance Anosmia and ageusia (Doty, 2012; Tarakad & Jankovic, 2017) Neuralgia (Rana et al., 2013) Urinary infection (Gerlach, Winogrodzka & Weber 2011) Depression, anxiety (Sveinbjornsdottir, 2016) |

| Factors that may influence | Increasing age (Hou et al., 2019) Family history Head Injury Cardiovascular diseases (Leszek et al., 2021) Environmental toxins (Vasefi et al., 2020) | Increasing age (Hou et al., 2019) Family history Head Injury Male gender (Picillo et al., 2017) |

| Onset ages | First symptoms usually appear in the mid-60s. Early-onset AD begin between the 30s and mid-60s (National Institute on Aging, 2017) | The average age is 60 years old, whoever younger than 50 is considered young-onset PD (Johns Hopkins medicine, 2021) |

| Current treatment | Medication Physical therapy Dietary control (Zhang et al., 2020) Deep brain stimulation (Krauss et al., 2021) | Medication Physical therapy Cognitive behavioural therapy (Egan, Laidlaw & Starkstein, 2015) |

| Life expectancy | After diagnosis, the average expectancy for remaining life is 3 to 10 years (Zanetti, Solerte & Cantoni, 2009) | The relevant comparator is 23.3 years for average onset age of 60 years old (Golbe & Leyton, 2018). PD does not obviously reduce the lifespan |

When it comes to epidemiology, four key elements come to stand revealed on the paper: how much, when, where and whom. From Statista (2021), Official death certificates are recorded to be 37 in 100,000 for AD and 10.3 in 100,000 in PD in 2019 in the United States. AD has turned into the seventh single biggest killer in the world (WHO, 2019) and the sixth leading cause of death in the United States (Alzheimer’s Association, 2020). Followed with AD, PD has become the second most common neurodegenerative disease (Lebouvier 2009).

Figure 1. Death rate from Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease in the United States from 2000 to 2019 (data is from Statista: John Elflein, 2021; Statista Research Department, 2021)

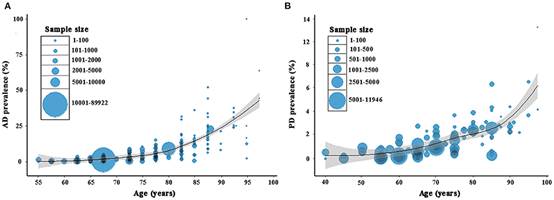

The factor “whom” I mentioned above can be illustrated briefly by the following considering ages, sex and so on. There is some evidence to suggest that age is the main risk factor for AD and PD (Hou et al., 2019). According to the research of Cui et al. (2020), the rates of both AD and PD grew consistently with age growing, but this phenomenon is more likely applicable for AD (Figure 2). Even though Cui et al. failed to account for worldwide data, it presents a positive correlation of prevalence of AD and PD as well as the slight difference between each other.

Figure 2. Prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease in China

(Cui et al., 2020)

It is a widely held view that females get more possibility at risk of developing AD, while males get a higher risk for vascular dementia (Podcasy & Epperson, 2016). Ample evidence suggests that female PD patients tend to show a more benign symptom for which many scholars hold the view that it is due to the consequence of oestrogen (Picillo et al., 2017). It is essential to bear in mind that there is a possible bias in the sex effect on AD and PD.

In the 1950s, researchers successively discovered that the presence of Lewy bodies in substantia nigra and locus nucleus patients in PD patients, gradually determining the pathological hallmarks of PD (Xiao-dan, 2017). One of the limitations with this explanation is that in some cases like a mutation of PARK-2, there are no Lewy bodies (Matsumine, 1999). The research team of Arvid and Isamu find that there are dopamine abnormalities in the brain tissue of PD patients then (LeWitt, 2015). According to Dickson (2012) and Kouli (2018), alpha-synuclein accumulates in Lewy bodies and neurites in the brain and peripheral nerves. And it can be pathological hallmarks of PD, in which case, the abnormal cytoplasmic deposits occur in cell bodies. Neuropathologically, senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles can be hallmarks of AD (Sengoku, 2020). Under the action of endonuclease, the cleaved-off extracellular part of APP is the amyloid-β protein (O’Brien & Wong, 2011). The amyloid-β deposition is another hallmark for AD. Analogously, AD and PD both have tau pathology. Braak (1991) holds the view that the magnitude and location of tau deposition might be related to clinical symptoms of AD. The tau pathology is also reported to have an impact on neurons and glia in PD (Dickson 2012). Several observations suggest that there is a link between the dysfunction, even partly, of the mitochondria or the oxidative stress and the neuropathology of AD and PD (Swerdlow, 2018; Jamwal, Blackburn & Elsworth, 2021). Succinctly, AD and PD share both similarities and differences (Table 2).

Table 2. Pathological hallmarks of AD and PD

| AD | PD | |

|---|---|---|

| Pathological hallmarks | Extracellular β-amyloid deposits, i.e., senile plaques Extracellular β-amyloid deposits, i.e., senile plaques (MSD manuals, 2020) Nerve cell death in hippocampus and prefrontal cortex (Akhtar & Sah, 2020) | Lewy bodies in the substantia nigra striatum (MSD manuals, 2020) Synuclein deposition Degeneration of neurons in substantia nigra, locus coeruleus and other brainstem dopaminergic cells (Hansen, 2021) |

All in all, there is a big difference between the pathological characteristics, the affected brain parts and the clinical symptoms of AD and PD. As global life expectancy has increased, proteinopathies of the brain, which particularly affect the elderly, have placed an increasing burden on society. AD and PD invade the patients’ intellectual and emotional health, thereby potentially destroying their lives and family life. AD and PD invade the victim’s intellectual and emotional health, thereby potentially destroying their lives and family. Since there is a long prodromal period, if we can diagnosis those in advance, earlier and timely treatment might be able to be applied (Ubeda-Bañon et al., 2020), thus, sufferings might be relieved. Both PD and AD get involved in broad regions of the nervous system, neurotransmitters and protein aggregation (Kalia & Lang 2015). The difference is that PD mainly happens in substantia nigra, locus coeruleus and other brainstem dopaminergic cells (Hansen, 2021) while AD typically starts in the temporal lobe, in more detail, hippocampus and prefrontal cortex (Akhtar & Sah, 2020). No matter how similar or different those diseases are, one issue is certain, it is our biologists’ duty to pull those suffers with PD or AD out of the hell.

Reference

Bayer, T. A. (2015). Proteinopathies, a core concept for understanding and ultimately treating degenerative disorders? Eur Neuropsychopharmacol, 25(5), 713-724. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.03.007

Lanuti, P. et al. (2020). Neurodegenerative diseases as proteinopathies-driven immune disorders. Neural regeneration research, 15 (5), s. 850. doi:10.4103/1673-5374.268971

Virchow, R. (1854). Handbuch der Speciellen Pathologie und Therapie

Luheshi, L. M., Crowther, D. C., & Dobson, C. M. (2008). Protein misfolding and disease: from the test tube to the organism. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology, 12(1), 25-31. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.02.011

Capriotti, T., & Terzakis, K. (2016). Parkinson Disease. Home healthcare now, 34(6), 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1097/NHH.0000000000000398

Simon, D. K., Tanner, C. M., & Brundin, P. (2020). Parkinson Disease Epidemiology, Pathology, Genetics, and Pathophysiology. Clinics in geriatric medicine, 36(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2019.08.002

Hayes, M. T. (2019). Parkinson’s Disease and Parkinsonism. The American Journal of Medicine, 132(7), 802-807. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.03.001

Lane, C. A., Hardy, J., & Schott, J. M. (2018). Alzheimer’s disease. European Journal of Neurology, 25(1), 59-70. doi:10.1111/ene.13439

Van Bulck, M., Sierra-Magro, A., Alarcon-Gil, J., Perez-Castillo, A., & Morales-Garcia, J. A. (2019). Novel Approaches for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease. International journal of molecular sciences, 20(3), 719. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20030719

NHS.uk. (2019). Parkinson’s disease - Symptoms.

NHS.uk. (2019). Alzheimer’s disease - Symptoms.

Tarakad, A., & Jankovic, J. (2017). Anosmia and Ageusia in Parkinson’s Disease. International review of neurobiology, 133, 541–556. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.irn.2017.05.028

Rana, A. Q., Kabir, A., Jesudasan, M., Siddiqui, I., & Khondker, S. (2013). Pain in Parkinson’s disease: Analysis and literature review. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery, 115(11), 2313-2317. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2013.08.022

Younan, D., Petkus, A. J., Widaman, K. F., Wang, X., Casanova, R., Espeland, M. A., Gatz, M., Henderson, V. W., Manson, J. E., Rapp, S. R., Sachs, B. C., Serre, M. L., Gaussoin, S. A., Barnard, R., Saldana, S., Vizuete, W., Beavers, D. P., Salinas, J. A., Chui, H. C., Resnick, S. M., … Chen, J. C. (2020). Particulate matter and episodic memory decline mediated by early neuroanatomic biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain: a journal of neurology, 143(1), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awz348

El Haj, M., Colombel, F., Kapogiannis, D., & Gallouj, K. (2020). False Memory in Alzheimer’s Disease. Behavioural neurology, 2020, 5284504. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/5284504

Boccardi, V., Ruggiero, C., Patriti, A., & Marano, L. (2016). Diagnostic Assessment and Management of Dysphagia in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease: JAD, 50(4), 947–955. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-150931

Teichmann, M., & Ferrieux, S. (2013). Aphasia(s) in Alzheimer. Revue neurologique, 169(10), 680–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurol.2013.06.001

Hennawy, M., Sabovich, S., Liu, C. S., Herrmann, N., & Lanctôt, K. L. (2019). Sleep and Attention in Alzheimer’s Disease. The Yale journal of biology and medicine, 92(1), 53–61.

Leszek, J., Mikhaylenko, E. V., Belousov, D. M., Koutsouraki, E., Szczechowiak, K., Kobusiak-Prokopowicz, M., Mysiak, A., Diniz, B. S., Somasundaram, S. G., Kirkland, C. E., & Aliev, G. (2021). The Links between Cardiovascular Diseases and Alzheimer’s Disease. Current neuropharmacology, 19(2), 152–169. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X18666200729093724

Vasefi, M., Ghaboolian-Zare, E., Abedelwahab, H., & Osu, A. (2020). Environmental toxins and Alzheimer’s disease progression. Neurochemistry international, 141, 104852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2020.104852

Picillo, M., Nicoletti, A., Fetoni, V., Garavaglia, B., Barone, P., & Pellecchia, M. T. (2017). The relevance of gender in Parkinson’s disease: a review. Journal of neurology, 264(8), 1583–1607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-016-8384-9

Egan, S. J., Laidlaw, K., & Starkstein, S. (2015). Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Depression and Anxiety in Parkinson’s Disease. Journal of Parkinson’s disease, 5(3), 443–451. https://doi.org/10.3233/JPD-150542

Zhang, M., Zhao, D., Zhou, G., & Li, C. (2020). Dietary Pattern, Gut Microbiota, and Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 68(46), 12800–12809. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.9b08309

Krauss, J. K., Lipsman, N., Aziz, T., Boutet, A., Brown, P., Chang, J. W., Davidson, B., Grill, W. M., Hariz, M. I., Horn, A., Schulder, M., Mammis, A., Tass, P. A., Volkmann, J., & Lozano, A. M. (2021). Technology of deep brain stimulation: current status and future directions. Nature reviews. Neurology, 17(2), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-020-00426-z

Zanetti, O., Solerte, S. B., & Cantoni, F. (2009). Life expectancy in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Archives of gerontology and geriatrics, 49 Suppl 1, 237–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2009.09.035

Golbe, L. I., & Leyton, C. E. (2018). Life expectancy in Parkinson disease. Neurology, 91(22), 991–992. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000006560

Hopkinsmedicine.org. 2021. Young-Onset Parkinson’s Disease.

National Institute on Aging. 2017. What Are the Signs of Alzheimer’s Disease?

Langer K. G. (2019). Early History of Amnesia. Frontiers of neurology and neuroscience, 44, 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1159/000494953

Sveinbjornsdottir S. (2016). The clinical symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Journal of neurochemistry, 139 Suppl 1, 318–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnc.13691

Querfurth, H. W., & LaFerla, F. M. (2010). Alzheimer’s disease. The New England journal of medicine, 362(4), 329–344. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra0909142

Burns, A., & Iliffe, S. (2009). Dementia. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 338, b75. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b75

Fang, E. F., Hou, Y., Palikaras, K., Adriaanse, B. A., Kerr, J. S., Yang, B., Lautrup, S., Hasan-Olive, M. M., Caponio, D., Dan, X., Rocktäschel, P., Croteau, D. L., Akbari, M., Greig, N. H., Fladby, T., Nilsen, H., Cader, M. Z., Mattson, M. P., Tavernarakis, N., & Bohr, V. A. (2019). Mitophagy inhibits amyloid-β and tau pathology and reverses cognitive deficits in models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature neuroscience, 22(3), 401–412. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-018-0332-9

Tolosa, E., & Compta, Y. (2006). Dystonia in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of neurology, 253 Suppl 7, VII7–VII13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-006-7003-6

Ganguly, G., Chakrabarti, S., Chatterjee, U., & Saso, L. (2017). Proteinopathy, oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction: cross talk in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Drug design, development and therapy, 11, 797–810. https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S130514

Hou, Y., Dan, X., Babbar, M., Wei, Y., Hasselbalch, S. G., Croteau, D. L., & Bohr, V. A. (2019). Ageing as a risk factor for neurodegenerative disease. Nature reviews. Neurology, 15(10), 565–581. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-019-0244-7

McGregor, M. M., & Nelson, A. B. (2019). Circuit Mechanisms of Parkinson’s Disease. Neuron, 101(6), 1042–1056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2019.03.004

Doty R. L. (2012). Olfactory dysfunction in Parkinson disease. Nature reviews. Neurology, 8(6), 329–339. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2012.80

Peter-Derex, L., Yammine, P., Bastuji, H., & Croisile, B. (2015). Sleep and Alzheimer’s disease. Sleep medicine reviews, 19, 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2014.03.007

Meireles, J., & Massano, J. (2012). Cognitive impairment and dementia in Parkinson’s disease: clinical features, diagnosis, and management. Frontiers in neurology, 3, 88. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2012.00088

Cui L, Hou NN, Wu HM, Zuo X, Lian YZ, Zhang CN, Wang ZF, Zhang X, Zhu JH. Prevalence of Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease in China: An Updated Systematical Analysis. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020 Dec 21; 12:603854. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2020.603854. PMID: 33424580; PMCID: PMC7793643.

Takizawa, C., Gemmell, E., Kenworthy, J. et al. A Systematic Review of the Prevalence of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Stroke, Parkinson’s Disease, Alzheimer’s Disease, Head Injury, and Pneumonia. Dysphagia 31, 434–441 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-016-9695-9

Number of deaths due to Parkinson’s disease | Statista. (2021). Retrieved 12 December 2021, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/753594/number-of-deaths-from-parkinson-in-spain/

Alzheimer disease mortality rate U.S. 2000-2019 | Statista. (2021). Retrieved 12 December 2021, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/452945/mortality-rate-of-alzheimers-patients-in-the-us/

Lebouvier T, Chaumette T, Paillusson S, Duyckaerts C, Bruley des Varannes S, Neunlist M, Derkinderen P. The second brain and Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Neurosci. 2009 Sep;30(5):735-41. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06873. x. Epub 2009 Aug 27. PMID: 19712093.

World Health Organization. The top 10 causes of death. (2019).

Alzheimer’s Association. (2020). 2020 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 10.1002/alz.12068. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12068

Podcasy, J. L., & Epperson, C. N. (2016). Considering sex and gender in Alzheimer disease and other dementias. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 18(4), 437–446. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2016.18.4/cepperson

Sengoku R. (2020). Aging and Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Neuropathology: official journal of the Japanese Society of Neuropathology, 40(1), 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/neup.12626

Braak, H., & Braak, E. (1991). Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta neuropathologica, 82(4), 239–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00308809

Swerdlow R. H. (2018). Mitochondria and Mitochondrial Cascades in Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease: JAD, 62(3), 1403–1416. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-170585

Jamwal, S., Blackburn, J. K., & Elsworth, J. D. (2021). Expression of PON2 isoforms varies among brain regions in male and female African green monkeys. Free radical biology & medicine, S0891-5849(21)00856-X. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.12.005

Kouli, A., Torsney, K. M., & Kuan, W. L. (2018). Parkinson’s Disease: Etiology, Neuropathology, and Pathogenesis. In T. B. Stoker (Eds.) et. al., Parkinson’s Disease: Pathogenesis and Clinical Aspects. Codon Publications.

Xiao⁃dan, W., Yong, J. (2017) 200⁃year history of Parkinson’s disease. Chin J Contemp Neurol Neurosurg

LeWitt P. A. (2015). Levodopa therapy for Parkinson’s disease: Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Movement disorders: official journal of the Movement Disorder Society, 30(1), 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.26082

Matsumine H. (1999). Rinsho shinkeigaku = Clinical neurology, 39(1), 9–12.

MSD manual: professional version. (2020). JAC-Antimicrobial Resistance, 2(3). doi:10.1093/jacamr/dlaa042

Akhtar, A., & Sah, S. P. (2020). Insulin signaling pathway and related molecules: Role in neurodegeneration and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochemistry international, 135, 104707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2020.104707

O’Brien, R. J., & Wong, P. C. (2011). Amyloid precursor protein processing and Alzheimer’s disease. Annual review of neuroscience, 34, 185–204. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113613

Ubeda-Bañon, I., Saiz-Sanchez, D., Flores-Cuadrado, A., Rioja-Corroto, E., Gonzalez-Rodriguez, M., Villar-Conde, S., Astillero-Lopez, V., Cabello-de la Rosa, J. P., Gallardo-Alcañiz, M. J., Vaamonde-Gamo, J., Relea-Calatayud, F., Gonzalez-Lopez, L., Mohedano-Moriano, A., Rabano, A., & Martinez-Marcos, A. (2020). The human olfactory system in two proteinopathies: Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Translational neurodegeneration, 9(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40035-020-00200-7

Hansen N. (2021). Locus Coeruleus Malfunction Is Linked to Psychopathology in Prodromal Dementia With Lewy Bodies. Frontiers in aging neuroscience, 13, 641101. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2021.641101